Entertainment

Essentials

Podcasting Essentials

Related articles:

At first, I thought it was a fluke.

The first review I ever got for Where the Stars Fell came at about the tail end of season one: a listener with dyslexia, like one of the main characters, and who was an ambulatory cane user, like the other main character, was casually enjoying the show up until episode seven. During the episode, Ed reveals she is “dyslexic to the point of functional illiteracy”, and explains how the American education system completely failed her in that respect. After that, the listener said, they just started crying. They had never seen representation like this before, of a dyslexic character with ADHD who was an incredible genius or of a cane user with a prosthetic leg who wasn’t ashamed of it, just tired of the way other people treated her. These experiences, and the care and clarity with which they were written, had never been found in the other media they had consumed. They were immensely thankful, and were excited for future seasons.

To be perfectly frank, I thought they were pulling my leg.

I thought they were giving me too much credit as a writer. I assumed they simply hadn’t had the luck of encountering what had to be plenty of other media that featured disabled representation as well, if not better, than this show. Surely, I decided, with audio drama’s progressive stance on representation and showcasing marginalized stories, there had to be many other fiction podcasts out there doing what I was doing.

Then I read more reviews. Countless Tumblr posts and Tweets. Some incredibly heartfelt and kind emails. And it sort of dawned on me that the issue was not me being given too much credit… we were just starving.

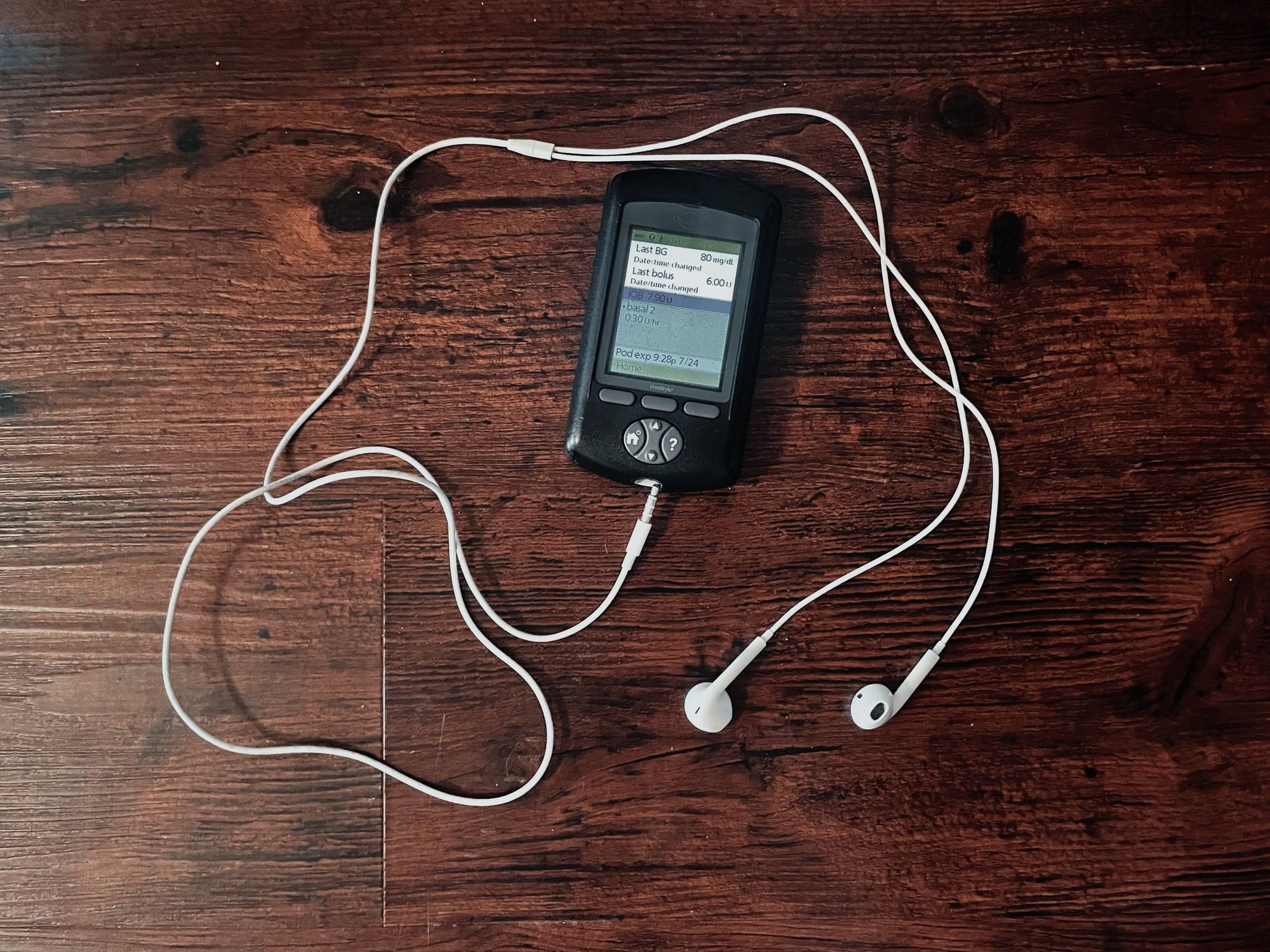

I’ve been autistic all my life, but wasn’t diagnosed with Type One Diabetes until my senior year of high school after I had already been developing Where the Stars Fell and its characters for a while. That experience not only changed my life and how I navigated the world–it changed the show. It made me want to tackle themes of identity, disempowerment, control, and what we as people do when we believe our choices have been taken away from us. No, I did not believe becoming physically disabled had ruined my life, but I was a teenager. You bet your britches I was going to find a way to complain about it.

In making Lucy an amputee with a prosthetic and a cane she uses for chronic fatigue and pain, I wanted to give her a disability that would be constantly present in an audio medium, and tirelessly researched how to do that accurately. From hiring a sensitivity reader, to listening to countless videos of cane and prosthetic users, to tinkering with the settings on my footstep plugin to replicate a prosthetic foot as well as a cane, I was determined to help our audience experience what every disabled person already knows: you don’t get days off from this. It’s there, every minute and every step of the way.

When it came to Ed’s dyslexia and ADHD, and to an extent with Lucy’s autism, I was well aware of how so many facets of our society consistently fail people with developmental disabilities (DDs). I was tired of characters with DDs being smart in some unconventional way like painting, strategy, or fixing cars. I wanted a character who, the moment they were given the proper support and resources they needed, instantly became the smartest person in the room. Ed Tucker can’t read, and three out of her four doctorates are in STEM. Deal with it.

The thing about starting out doing something out of spite, however, is that you often don’t realize the ways in which it can impact others. I forgot that when marginalized creators are allowed to tell their stories fully and freely, we are able to put into our art what so many of us have always been feeling. Equally important, I also forgot that humans, at their core, are good people, and most abled people will welcome the chance to be educated on what they don’t know, and how they can help.

We can only go about making art once our basic needs are met, and so many would-be storytellers are kept out of creative spaces by having to struggle to make ends meet.

In my view, there are two kinds of good stories centered around disability: ones that seek to educate, and ones that seek to empower.

Stories that seek to educate have the goal of showcasing or explaining an aspect of the disabled experience, whether something specific to a condition or a more universal one, so those who are unfamiliar with it can learn and take action. A great example of this is the episode of Someone Dies In This Elevator, “Hot Wheels”. The premise is simple, but effective: two wheelchair users are trapped in an elevator during a building fire. Because there are no systems in place to rescue them, and they are unable to take the stairs, they die. A devastating situation that happens every day because of the society we live in, and something that many people who use mobility aids have to either plan for, or hope will never happen to them. Those who can relate to this episode don’t need to be taught this, and some may even justifiably skip it because they don’t want to experience the anxiety and trauma that comes with listening. But abled people, and to an extent those who don’t use mobility aids? Those people need to listen to this episode, because it educates them on an all-too-real scenario that they can advocate to help prevent.

The second type of story is entirely focused on empowering the disabled members of its audience. This can be through a variety of ways, from showcasing a power fantasy that doesn’t erase or “cure” the disabled character(s), to depicting them receiving support, comfort, or catharsis, to just reminding disabled viewers that they’re not alone through the depiction of relatable experiences and feelings.

There are a small handful of other audio dramas with disabled characters: The Way We Haunt Now, We Fix Space Junk, and This Planet Needs A Name to list a few. Where the fiction podcast industry’s catalog is hurting, however, is shows that feature disabled characters in the spotlight, and whose plot and/or themes specifically revolve around their disabled experience. This is a tricky task, of course. You want to create a story that is realistic and earnest in its depiction of what being disabled is like, but with a lead that is not entirely defined by their disability. For abled creators, this struggle can result in them messing up, which leads to a fear of even trying at all. For disabled creators, it’s a matter of convincing people that the way we live our life is a viable situation for a protagonist to be in.

A show that I feel does this exceptionally well is Seen and Not Heard. Creator Caroline Minks is a member of the Deaf/HoH community, and worked with sound designer Tal Minear to craft an audio drama that portrays their experience and how they hear the world. It seeks to both educate hearing listeners on what that experience is like, and connect with its Deaf/HoH listeners to let them feel represented and understood. On this balancing act, Minks said, “I didn't want the show to turn into one of those ‘see what it's like to be disabled for a day’ experiments you see on YouTube, but I did want to take advantage of the audio medium and give a hearing audience a taste of what it's like for people like Bet (and, by extension, me)”.

In the third episode, Bet stands up to her mother and advocates for herself, which Minks cited as an important moment for empowering disabled listeners. “It's the kind of thing a lot of us want to say to abled people in our lives,” they explain, “and my hope was that even if we aren't all able to do so, that the scene would serve as a bit of catharsis”.

If abled creators want to do their part– good on you! There’s an immediate option available: support the disabled writers telling their stories right now, and not just by listening to their shows and telling a friend. Post about them and leave the show a review so listeners are more likely to add it to their queue. Donate to crowdfunds to make another season or a new project. Outside of the internet, see what resources your community offers disabled folks and how you can help support them. We can only go about making art once our basic needs are met, and so many would-be storytellers are kept out of creative spaces by having to struggle to make ends meet.

For abled creators who want to feature disabled characters in their stories, whether physically or developmentally, you need to get a sensitivity reader and pay them (remember, you’re asking someone to advise you from an experience of oppression. Compensate that emotional labor). If you have disabled actors in mind to play these characters, great! If you’re able to cast disabled actors after the fact, also great! Just remember that it is against the law to force someone to disclose their status as disabled, and just as if this were a person on the street, you do not have the right to demand that information from anyone.

The most important thing to remember is that, at the end of the day, we are people made up of a myriad of experiences, some of which happen to include having one or more disabilities. The first thing I do when I wake up is check my blood sugar. The second thing I do is check Twitter.

I have always considered Where the Stars Fell the story I needed to tell because of what I was going through at the time, and how I best process my thoughts and feelings. I still think that, but with an addendum: Where the Stars Fell is the story I needed to tell because disabled people need to have our stories told in full, unapologetic color. We need the moments of power fantasy, like Lucy using her wings to balance as she takes out a demon with her giant sword, not forgetting her disability, but accounting for it as she goes in for a supremely cool move. We need the moments of relatable realism, like Ed switching up the screen reader voices on her computer to keep from getting bored. We need the moments where we ourselves learn important lessons, like Maggie reminding Lucy, one autistic person to another, that the world does not exist in black and white, and you cannot control every unfamiliar scenario. We need to be treated like every other listener– like people– because so far, we haven’t been. But that can change. I see it changing right now, and I will always consider myself so lucky to be a part of it.

Newton “Newt” Schottelkotte (they/them) is a producer, sound designer, VA, and all-around podcasting person from Nashville, TN. In addition to writing about podcasts, they produce them, including Where the Stars Fell, Mini Marconis, and Inkwyrm, as the head of Caldera Studios, and can be found sharing their skills and love for audio storytelling throughout the audio drama community. Newt enjoys getting outdoors, knowing way too much about the history of country music, and attempting to be funny on Twitter. Find out more about Newt on their website.