Entertainment

Related articles:

Short answer: Probably not. Let’s talk about why.

Immersive and immersion have become buzzwords in scripted podcasting, whether describing complicated sound design on a spaceship or a true crime script that “makes you feel like you were there!” It’s become so popular that its meaning has become so uselessly nebulous to the point that Simplecast has actually directed its writers to avoid the term entirely.

What is “Immersion”?

On the creator’s side of things, immersion typically means a clear story with detailed sound design that really captures the listeners attention, pulling them into the story and making it easy for them to visualize the events happening in their headphones. Oftentimes it’s used to describe the panning of audio from one headphone to another, especially as characters move between environments.

But on the industry side of things, by which I mean the domain of audio engineers, programmers, and game developers, “immersion” has a vast but pretty strict set of definitions–and most podcasts that use the term don’t meet them.

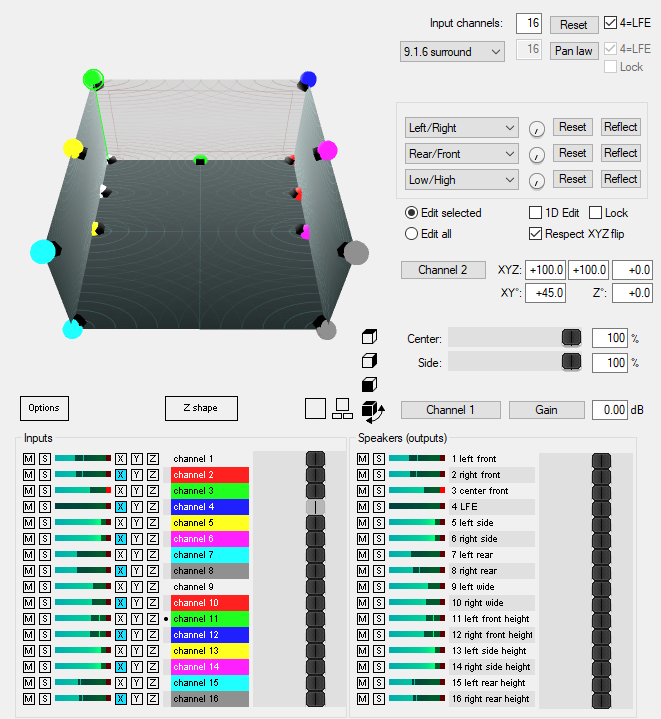

“Immersive Audio” generally means one of two things: A lot of speakers, or a bunch of math to make it seem like there’s a lot of speakers. Either way, the end goal is the same: allow the listener to get the impression that a sound is coming from any point within the virtual “room” that they’re listening in. If you’re thinking that’s the same as panning, it’s actually a lot more complicated. While simple stereo panning allows a signal to move along a Left-Right axis, immersive audio should allow the engineer to put a voice left, right, in front of, behind, above, below, or any combination thereof relative to the listener.

So how is that actually done?

More Speakers: Multichannel Audio

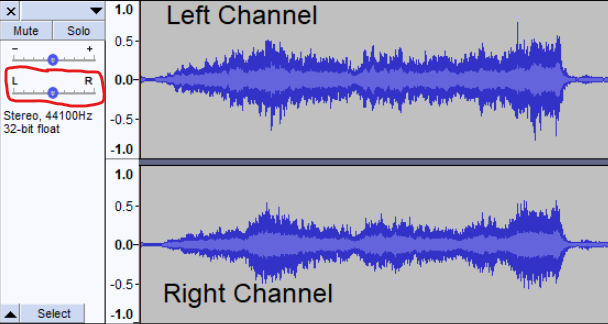

You’re probably already familiar with Stereo Audio, which has two channels, Left and Right (L and R), as it’s what the overwhelming majority of audio files are delivered as in consumer markets. It’s also what your L/R panning knobs are going to influence.

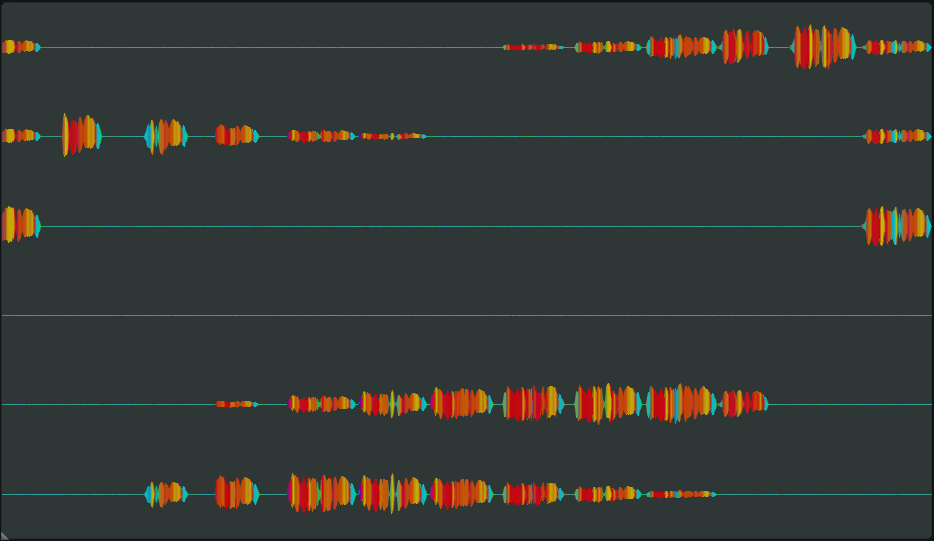

Multichannel audio simply adds additional channels that route to additional speakers, which you’ve probably encountered in the form of 5.1 or 7.1 surround sound.

Using surround sound, the listener does get the feeling that a sound is coming from behind them because, well, some of the speakers are actually behind them. The problem is that in addition to not being very portable, surround systems are expensive. Entry level 5.1 setups (which have 5 speakers and a subwoofer) typically run $200, while more fully immersive 9.1.6 systems (which have a total of 16 speakers) can easily pass $20,000 and are typically only installed in movie theaters, professional mixing studios, and temporary immersive audio exhibits.

More Math: Immersive Stereo

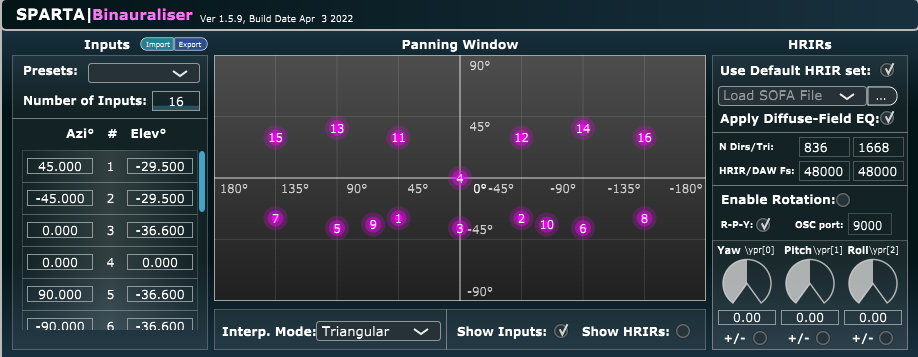

Since actual surround sound setups tend to be prohibitively expensive and not portable, a lot of consumer end immersive audio is built for headphones, typically called a binaural mix (meaning “two ears”). This is where the math comes in. There’s 50 years of it, so I’m leaving the actual numbers out.

A sound from directly behind you will hit the back of your head and ears before reaching your eardrum, meaning the sound will be slightly filtered by the outside of your ear and you’ll hear the reflections of the room just a little bit more than if the sound came from in front of you. A sound to your right will reach your left ear just a little later and quieter than your right one–something our brains are able to use to figure out where a sound is coming from in relation to our heads. Whatever tool you use to make something immersive, whether that’s an ambisonics decoder for VR mics like the Sennheiser AMBEO or a room encoder like dearVR Micro, they’ll be giving your audio signal the proper pan, equalization (EQ), and room reflections (which will get their own pan and EQ information) to make it sound like it’s wherever you want it to be in a 3D space, even though it’s actually coming from fixed speakers next to your ears. There’s actually arguments among professionals about mixing to individual people’s ears and heads, but I’m not going to get into that here.

That sounds complicated.

It is, and it’s expensive. Sound designing a scripted show that’s actually using immersive audio is likely to take 3-5 times as long as the same one in simple stereo, because the exact spatial placement of every single audio file needs to be considered. And a lot of the time… you don’t need to. Most listeners are content with basic Left-Right panning, and unless you want the marketing power of having the words “Mixed in Dolby ATMOS” in your press kit, you’re just going to be putting a lot more work (or a lot more money) into your show for very, very little return on investment.

Want to learn more about immersive audio? Check out the Immersive Audio Podcast from 1.618 Digital.

What To Use Instead

No one wants to give up the marketing power of “immersive.” I get it, especially with Apple rolling out Spatial Audio updates to their hardware and a whole bunch of music being rereleased in Dolby ATMOS, it seems like immersive is the go-to word for anything audio. But if a show doesn’t use immersive audio tools, don’t call it immersive. Call the sound design “lifelike,” the story “vivid”, or even just call the show “amazing.” You don’t need to overhype it.

Brad Colbroock is a SoCal podcaster and foley artist with a passion for audio drama. They are currently helping to produce upcoming shows for Parazonium Podcasts and The Shadow Network. You can hear Brad's sound design in The Way We Haunt Now, Someone Dies In This Elevator, and SPECTRE.