Entertainment

Related articles:

Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE) council member Sasha Stewart branched out into writing for scripted fiction podcasts a few years ago, not uncommon a shift for TV writers these days. “It was an absolute delight,” she recalled, “but I recognized pretty quickly that I was doing a lot of the same kind of work that I would be doing writing on a television show, but I was getting paid about a tenth of what I would get paid to write a television show.” And this, unfortunately, is also not uncommon in the industry, where podcast projects are underfunded and understaffed to the detriment of everyone – from producers to cast to writers.

In late 2020, the WGAE launched a new solidarity and organizing initiative called the Audio Alliance, specifically geared towards setting the standard for scriptwriters across the audio industry. The movement was first spearheaded by WGA members Matt Klinman, Dru Johnston, and James Folta. Klinman had spoken briefly to the WGAE President at the time, Beau Willimon, about the scripted audio shows he’d been working on that hadn’t contributed to health insurance nor pension because they weren’t WGA covered. A few months later, he ran into Johnston and Folta at a Banh Mi shop, where Johnston expressed delight that Willimon and others at the WGA were finally paying attention to the idea of covering podcasts.

We’re proud to announce the formation of the @WGAAudio Alliance. As our industry grows, we’re excited to support the writers who make great audio fiction possible. @wgaeast #audiodramasunday #audiodrama #podcasts pic.twitter.com/NdudXOSz6G

— WGA Audio Alliance (@WGAAudio) October 11, 2020

They started with just a few members joining the organizing committee via Zoom for monthly meetings and a database of scripted audio writers who were in the Alliance, which quickly became a potential hiring list. These days, they have more than 500 members, which includes both WGA members and independent creators. There's also a Discord server for active organizing, a growing Twitter account where they promote solidarity with fellow unions within and outside the industry, and regular webinars and panels meant to encourage and educate creators in their process.

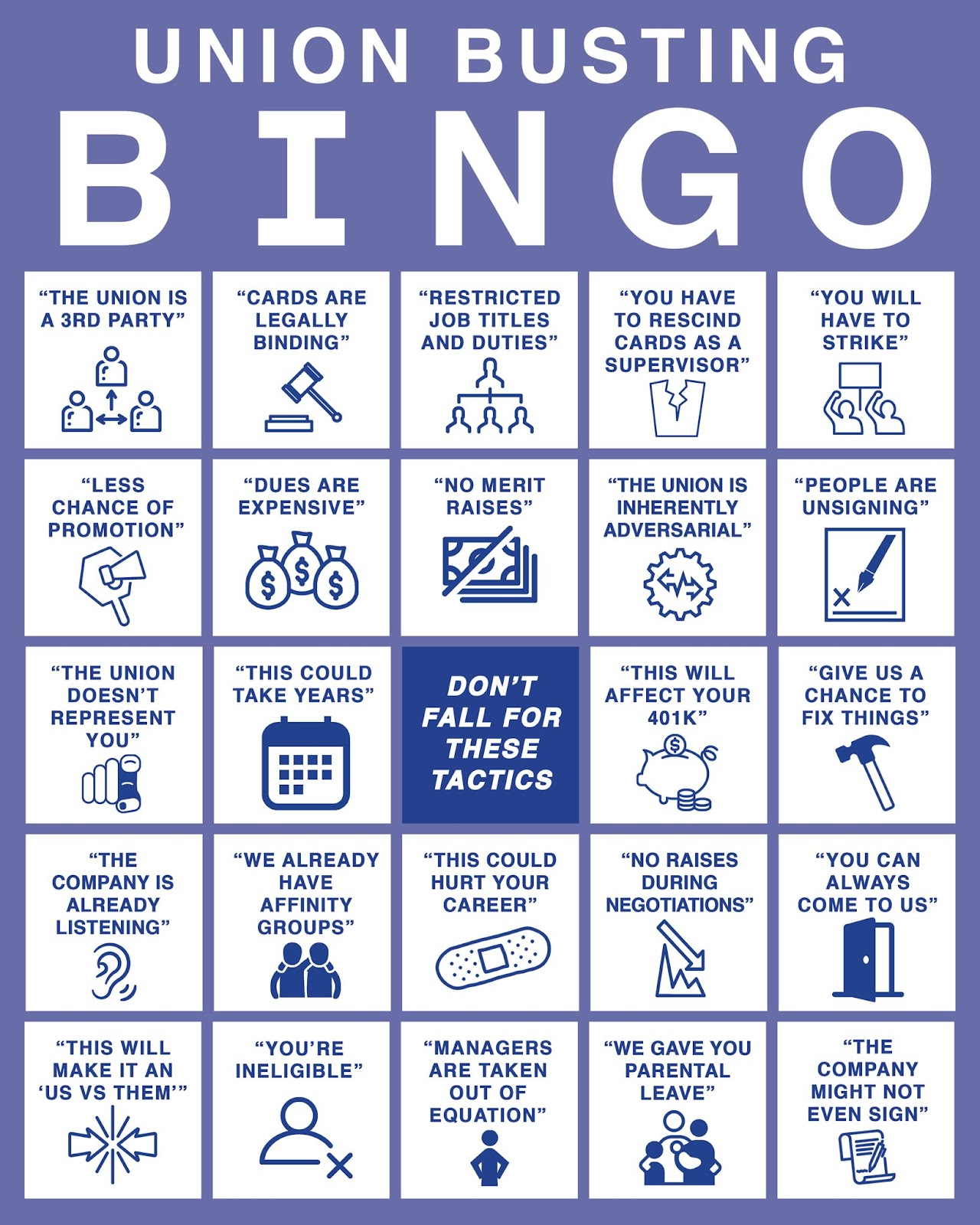

But one of the key issues the Audio Alliance is facing is a messaging problem that a lot of unions face: who, exactly, can join in on this effort? There’s a popular, false conception of unions as massive gatekeepers who want to ruin the lives of your regular, independent, working-class person; messaging that has been used by union-busters over and over again.

“One of the fundamental misunderstandings of unions, especially in the creative and independent sphere is that if a union exists, then they’re going to come after somebody who’s doing something on their own and say that you aren’t allowed to make this podcast because you can’t pay your writers,” Stewart describes. “That’s not true.” Stewart points out that the WGA already has different standards for indie filmmakers and small-budget features than they do for big budget features.

Unions, she says, are for going after giant companies who exploit writers and tell them, “you have billions of dollars, you need to pay the people who are creating content for you fairly.” Not for going after the scrappy, independent creator – in fact, the union is built to hopefully help that scrappy creator down the line, when they get hired by one of these big companies and get paid an equitable rate, the standard of which has been set down by previous organizers.

“If it had been a union contract,” Stewart describes of her previous experience, “I would have been eligible for health care…I was doing all this writing and I thought, why isn’t this money going towards my health insurance benefits?” Not only would it have benefitted her, but it would have benefited others: “I had hired three writers to work with me and my writers’ room. And if it had been a union show, then all three writers who are not part of the Writers Guild…would have made enough to qualify to join, and then they also would have gotten health insurance.”

Every single issue is a labor rights issue.

The Audio Alliance is built to create and foster solidarity in order to gather the traction and voices necessary to do that. WGAE strategic organizer Dana Trentalange describes the Audio Alliance as unique, since they aren’t focused on winning standard union elections. “Instead, we’re approaching transforming the industry by lifting rates and standards from a community organizing perspective,” and Trentalange’s role in this is crucial for the Audio Alliance’s connection to the WGAE. She helps members plan and implement social events, career development opportunities, and trainings in order to disseminate the WGAE’s institutional information and share the perspective that “the only way to improve standards for everyone in the industry is to face these issues collectively.”

It’s not a surprise that the Audio Alliance is taking a novel approach within the industry; the most common, tired refrain within podcasting is that it’s the “Wild Wild West” of entertainment media. Part of the reason for this is that there are no industry-specific standards for almost anything: not for paying writers, crew, or cast, not for marketing strategies, not for cultural and entertainment criticism and critical language. In fact, the Interactive Advertising Bureau’s Podcast Technical Working Group published the first set of Podcast Measurement Technical Guidelines in 2016, with the most recent version finalized in early 2021. Until this point, podcast metrics have been at the whim of the app and distributor in question, and to some extent still are. While this means there is opportunity for creative solutions and experimentation, it also means the people most likely to be hurt by this are freelance creators who create content for a company and are paid far less than their peers in television or film for essentially doing the same amount and type of work.

Which brings us to the core question of the Audio Alliance work in attracting members who are not already Guild members: what is this alliance actually designed to do? Stewart describes the Alliance’s primary work as information sharing, because “sharing information is absolutely vital towards getting better wages, and getting better treatment and better contracts overall. Because if you share the information on your contract, somebody else knows, 'oh, wow, I was getting paid, you know, definitely less on my contract for the same company, I know to ask for more next time.'”

We're organizing because the only way to change the exploitation of creatives in this industry is collective action. pic.twitter.com/XCZX1kwGZj

— WGA Audio Alliance (@WGAAudio) July 5, 2022

That information sharing is one of the key ways that creators in the industry can raise not only the standard of pay for everyone, but grant the inclusion of other crucial components, such as derivative rights. Derivative rights in podcasting are already front and center in the fight for equitable treatment, as we see more and more podcasts get adapted into TV and film and more and more companies trying to avoid giving creators derivative rights. Derivative rights ensure that people who create a work keep their names credited on all adaptations of that work down the line, and don’t get their names, history, and work erased. “Your name should be attached to that intellectual property forever, and no matter what else it is derived into,” Stewart explained firmly.

The concept at the core of the Audio Alliance is solidarity. Solidarity within the Alliance, the union, and the struggles that those in the working class face. When I asked Trentalange to describe what she means when she says ‘solidarity,’ she replied: “To me, solidarity means working class unity, full stop.”

One of the Audio Alliance’s first objectives was to consider truly equitable and just diversity and inclusion, one that takes into account people’s realities and lived experiences and not just faces of people of color in a photo on a press release. “[T]he labor movement cannot effectively continue to treat attacks on the trans community, abortion rights, voting rights, and gun control as ancillary to workers’ rights. Every single issue is a labor rights issue. Unwavering solidarity in the face of such attacks is the only way to effectively put an end to them as long as we live in a capitalist system,” said Trentalange.

With the recent highly conservative rulings from the SCOTUS regarding things like abortion rights, gun laws, and the right to sue the government for failing to Mirandize, understanding the depth and breadth of what solidarity means is crucial. We can’t fight these battles alone. Together, in solidarity with each other, we can push our paths forward.

Are you planning to become or are you currently a podcast writer? You can join the WGA Audio Alliance; you do not need to be a member of the WGA. All the relevant links are right here.